How Do You Solve a Problem Like IGRA? Assessing Tribes v. Kalshi And Robinhood

Back in April, I described the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) as “the elephant in the room” for sports prediction markets. Well, the elephant’s now trumpeting — three federally recognized Indian Tribes have sued Kalshi and Robinhood in California.

Will the Tribes notch a win over Kalshi? Or will their case be the latest “W” in Kalshi’s win streak? I honestly can’t say. But what I can do is unpack what this case is about, and raise some questions about the legal claims.

Here’s the crux of the Tribes’ legal theory, as I understand it. Kalshi offers sports-event contracts. (At this point, we all know what those contracts look like.) Kalshi’s contracts don’t comply with the requirements of the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA), as they’re barred by Rule 40.11. Because Kalshi’s contracts “fall outside the permissible scope of the CEA,” they “constitute unlawful gambling in Indian country.” Compl. ¶¶ 48, 151, 152, 154.

The Tribes’ Complaint presents five claims:

an IGRA violation

a violation of tribal gaming ordinances

a violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or what my fellow lawyer Popehat calls “doing a RICO”

infringement of the Tribes’ sovereignty and interference with tribal self-governance

the Lanham Act.

I’m going to dive into the first and fifth claims because they speak to issues that I know a little about (emphasis on little), and RICO basically requires me to do this:

(In other words, RICO is … complicated. And so is the Tribes’ RICO claim. We can do a separate post on the RICO, but tl;dr: in this instance, if it’s not gambling, it’s not a RICO.)

With that, let’s dive in.

The IGRA claim

The Tribes’ leading argument is that Kalshi’s sports-event contracts violate IGRA because sports wagering is Class III gaming activity, the contracts are essentially sports wagering, and Class III gaming may only be offered on Indian lands by a federally recognized Indian tribe in accordance with a tribal-state compact.

So far, so good. IGRA says “Class III gaming activities shall be lawful on Indian lands only if such activities are … conducted in conformance with a Tribal-State compact entered into by the Indian tribe and the State.” 25 U.S.C. § 2710(d)(1)(C). Class III gaming is defined as “all forms of gaming that are not class I gaming or class II gaming.” 25 U.S.C. § 2703(8). And the federal regulations implementing IGRA define “Class III gaming” as “[a]ny sports betting and parimutuel wagering.” 25 C.F.R. § 502.4.

But from here, the argument becomes harder to follow. The IGRA count alleges:

151. Through self-regulation, Kalshi has offered sports event contracts that are explicitly prohibited under 17 C.F.R. § 40.11(a)(1), and Kalshi has admitted that the subject matter of those contracts constitutes gaming.

152. Kalshi’s self-certifications of its sports event contracts, pursuant to 17 C.F.R. § 40.2, are defective because the submissions fail to adequately address CEA compliance issues and establish that the prohibited contracts are nevertheless CEA-compliant and are, therefore, not contrary to the public interest.

…

154. Kalshi’s contracts fall outside the permissible scope of the CEA and therefore, constitute unlawful gambling in Indian country under 18 U.S.C. § 1166, because the Kalshi app may currently be accessed for the purpose of staking something of value (consideration), on a sports event involving the element of chance, for the purposes of receiving a reward based on the outcome of the event, consistent with the definition of Class III gaming activity in 25 C.F.R. § 293.2(d), from locations in Indian country, as defined by IGRA, 25 U.S.C. §§ 2703(4)(A)-(B).

This comes across as the Tribes using IGRA to enforce the CEA. They seem to be arguing that, because these contracts don’t comply with the CFTC’s rules, Kalshi’s contracts (1) aren’t lawful event contracts, (2) aren’t subject to the CEA, and therefore (3) constitute illegal gambling and unauthorized Class III gaming.

I don’t think IGRA is really intended for that purpose — to enforce the requirements of the CEA. The Tribes will surely argue that they are vindicating the principles of tribal sovereignty enshrined in IGRA, not the CEA, and that they’re only making this argument to show that these contracts are fair game for an IGRA claim. But for the court to get there, it has to conclude that “Kalshi’s contracts fall outside the permissible scope of the CEA” because the contracts are not “CEA compliant” and thus “contrary to the public interest” under Rule 40.11. Compl. ¶¶ 152, 154. And the CEA has a remedy for that: the CFTC places the contracts under review. 7 U.S.C. § 7a-2(c)(5)(C)(i), (ii), (iv); 17 C.F.R. § 40.11(c). Kalshi may argue that CFTC review is the only remedy.

I also wonder if this claim is more complicated than it needs to be. After all, even in their CFTC-”approved” form, couldn’t sports-event contracts be “forms of gaming” because they function like bets or wagers? Even if these instruments are CFTC-regulated derivatives, that doesn’t make them any less “forms” of gaming — a derivative is a form. Sure, Kalshi could argue that a swap can’t be a “form of gaming,” but why? With respect to statutory text, the argument that “contracts … involving gaming” can also be “forms of gaming” under IGRA would place prediction markets in a sticky wicket.

One final thought on IGRA: It’s possible that we’ll see a technical fight about whether the Tribes can bring an IGRA claim at all. IGRA provides a cause of action “initiated by a State or Indian tribe to enjoin a class III gaming activity located on Indian lands and conducted in violation of any Tribal-State compact entered into under paragraph (3) that is in effect.” 25 U.S.C. § 2710(d)(7)(A)(ii).

Let’s break that down into a checklist.

✅ Initiated by a State or Indian tribe

✅ To enjoin a class III gaming activity

✅ Located on Indian lands

❓ Conducted in violation of any Tribal-State compact

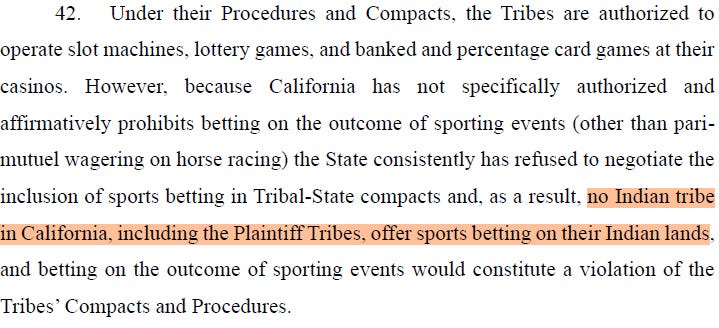

The Tribes’ allegations on how Kalshi’s contracts violate their compacts … could use more development. In fact, the Complaint alleges: “the State consistently has refused to negotiate the inclusion of sports betting in Tribal-State compacts and, as a result, no Indian tribe in California, including the Plaintiff Tribes, offer sports betting on their Indian lands.” Compl. ¶ 42. To be sure, the Tribes do allege that “Kalshi violates the Tribes’ Compacts,” Compl. ¶ 43, but the allegations don’t really say how.

If the Tribes’ theory is one of non-authorization, i.e., that Kalshi’s contracts violate tribal compacts because no compact authorizes them, they’ll need to explain how the absence of a compact necessarily translates into a violation of a compact, as § 2710(d)(7)(A)(ii) requires.

The Lanham Act

Ah, the Lanham Act. A law with a name that makes you think of a Gilded Age episode. It’s like the Swiss Army knife of unfair competition. Someone’s infringing on your trademark? Lanham Act. Someone’s squatting on your domain name? Lanham Act. Jasper, take us home:

The Tribes allege a false advertising claim under the Lanham Act, pointing to Kalshi ads that describe Kalshi’s contracts as “betting,” and the platform itself as “the First Nationwide Legal Sports Betting Platform.” (I feel like I know a guy who covers this…) The Tribes say that these ads deceive “consumers into believing that Kalshi was associated with or created as a gambling platform affirmatively endorsed by the federal government.” Compl. ¶ 225.

That all sounds fine, except:

In other words, the Tribes’ Lanham Act grievance is that Kalshi is wrongly advertising itself as “a legally compliant sports betting platform,” Compl. ¶ 226, but the Tribes themselves aren’t in the space. The Lanham Act requires you to show that you’ve been injured by the allegedly false advertisement. You don’t need to be direct competitors (so sayeth the Supreme Court), but you still have to show some kind of direct injury. We’ll see how the Tribes make that showing, especially in light of the allegation above. I wouldn’t count out the Tribes in finding a way, especially given the unique issues relating to their sovereignty.

What’s next?

(All of you, reading this long, boring legal post.)

As of the time of publication, the Tribes haven’t filed a motion for a preliminary injunction (even though their Complaint nominally asks for one, Compl. ¶ 1). Why does that matter? A preliminary injunction motion means getting answers quickly on the parties’ likelihood of success on the merits. In other words, some answers—fast. (But faster doesn’t necessarily mean better — see Nevada and New Jersey.)

Without a preliminary injunction motion, it’ll be months before we see any major developments in the Tribes’ case. The beats are pretty familiar to any litigator. Kalshi and Robinhood will probably move to dismiss. The Tribes will file an opposition. Kalshi and Robinhood will file a reply. The judge issues a decision and the lawsuit’s either dismissed, or it keeps going. At some point, maybe summary judgment. A trial. An appeal. And so on.

In other words, don’t expect any definitive answers soon.

That said, one thing’s for sure: The fight with the tribes is here. And we’ll be watching.