Kalshi’s New Jersey Win: Looking For Answers? Too Bad.

Kalshi is gaining momentum in its legal battles against state gaming regulators. But if I were Kalshi, I’d be careful about charging into court while riding paper tigers. Kalshi’s latest win in New Jersey does little to shape the discourse on the future of sports event contracts.

The shaky foundation of Kalshi’s New Jersey win

Yesterday, Judge Kiel of the District of New Jersey handed Kalshi its second win in federal court, issuing a preliminary injunction that prevents New Jersey gaming officials from pursuing enforcement actions against Kalshi “concerning its sports-related event contracts.”

It’s a win, to be sure – but a tentative one, at that. My reaction to the decision:

I’ll not mince words: I think the decision is poorly reasoned, and I don’t know if it’ll hold up on appeal. Here are four reasons why.

First, the breezy 16-page opinion has four pages of analysis on the legal merits (the “likelihood of success” analysis). Four. I don’t have to look very hard to know that the State’s arguments got short shrift.

Second, the opinion borrows too much from the Nevada decision. Call me old fashioned, but I’m a firm believer that a judge should call balls and strikes based on the pitches he sees, and not rely on the calls that another ump made during yesterday’s game. To be sure, the Nevada case is relevant – but it shouldn’t be the starting point of the court’s analysis. But that’s what we saw in New Jersey: Judge Kiel’s “legal analysis” begins with the Nevada decision. The State wasn’t arguing against just Kalshi; it was arguing against Kalshi and Judge Gordon in Nevada.

As an aside, I think it’s … generous to say that the Nevada and New Jersey cases presented “similar preemption arguments,” as Judge Kiel did. “Similar” is doing a lot of work there. Compare New Jersey’s brief to Nevada’s, and you’ll see why. The State made a few arguments that Nevada didn’t make (or didn’t make as well) – this decision gives those arguments the back of the hand.

Third, the opinion reads as if it’s half-baked. Take the middle of page 10. Judge Kiel says the fact that the Commodity Exchange Act might expressly preempt certain state laws in certain situations doesn’t mean it can’t preempt state laws in other ways. Fair enough. He ends with a dramatic-sounding line: “My task is to look deeper.”

Does he look deeper? No. The decision hopscotches to a provision of the Commodity Exchange Act – a savings clause that says the “exclusive jurisdiction” provision doesn’t “supersede or limit” jurisdiction conferred by State law. Judge Kiel explains that this provision doesn’t mean state law isn’t preempted by the CEA because of the preceding phrase, “except as hereinabove provided.”

Or, consider what the decision says about Kalshi’s economic consequences argument. Judge Kiel rejects the State’s position that “sporting events are without potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence.” He says: “On the record before me, I disagree.” Usually, what would follow this kind of a sentence is a citation to some fact in the record. What does Judge Kiel cite? A law review article. (We’ll get to that article in a minute.) He then goes on to say, “Kalshi references a few recent examples of the economic impact of sporting events in television, advertising, and local communities.” The “record” supporting those references is a Golf Digest article about Rory McIlroy, and a Times Union article about Saint Peter’s 2022 Cinderella run.

So, when Judge Kiel says, “on the record before me,” I have to ask, “what record?”

Fourth, and finally, the decision relies too much on outside sources. Look, there’s a time and a place for law review articles. But you don’t have to be a lawyer to see how much outside research went into this decision. Whenever I see this many law review articles and secondary sources cited in an opinion (a short one, no less), I wonder about the opinion’s strength.

One article in particular, “States’ Big Gamble on Sports Betting” by Dave Aron and Matt Jones, sticks out. (At the time of the article’s release, both were CFTC lawyers.) Published in 2021, the article takes the position that the CFTC “may have jurisdiction over some traditional sports bets because such bets can be viewed as binary, other options, or other types of swaps. These bets may also constitute event contracts if they are listed on or cleared by a CFTC-registered entity.” It’s an interesting read, to say the least.

This is also the article that Judge Kiel cites in support of Kalshi’s “economic consequence argument” – pages 79-80, in fact. Let’s flip to those pages, shall we?

“The second part of this prong (a potential, financial, commercial, or economic consequence) may or may not also be met.”

Huh. The article goes on to quote the now-nominee for CFTC Chairman, Brian Quintenz, who said, “practically any event has at least a minimal financial, commercial or economic consequence.”

In other words, maybe the outcome of that regular-season MLB game has an economic consequence – if you squint really hard.

“Nothing is gambling, everything’s a commodity”

Dustin recently wrote a Closing Line article titled, “Nothing is Gambling, Everything is Gambling.” In the minds of CFTC-oriented folks like Messrs. Quintenz, Aron, and Jones, maybe it’s more: “Nothing is gambling, everything’s a commodity.”

I read the Aron and Jones article as suggesting that it’s the states that have been stepping on the CFTC’s toes all along, and that the CFTC can and should regulate some forms of sports betting. Not “sports contracts” – betting. The very last line of the article reads: “the authors believe it is likely that the CFTC will permit sports betting products subject to its regulation in some form.”

I don’t blame a pair of derivatives lawyers for thinking that the CFTC is the center of the universe. I’m also not going to get into the legal and technical reasons why a CFTC-centric approach to sports betting is immensely problematic. We have time to discuss all that at some roundtable, somewhere, someday.

But so far, we’ve danced around the difficult issues presented by Kalshi’s lawsuits – and Judge Kiel’s decision just compounds the problem. Kalshi’s drawn a line in the sand of “economic consequence,” and it claims that its contracts fall on the right side of the line – the CFTC’s side. We still don’t know, however, how definite that line is, whether it embraces all of Kalshi’s sports contracts (as Kalshi claims), and how hard you’re allowed to squint to find an economic consequence.

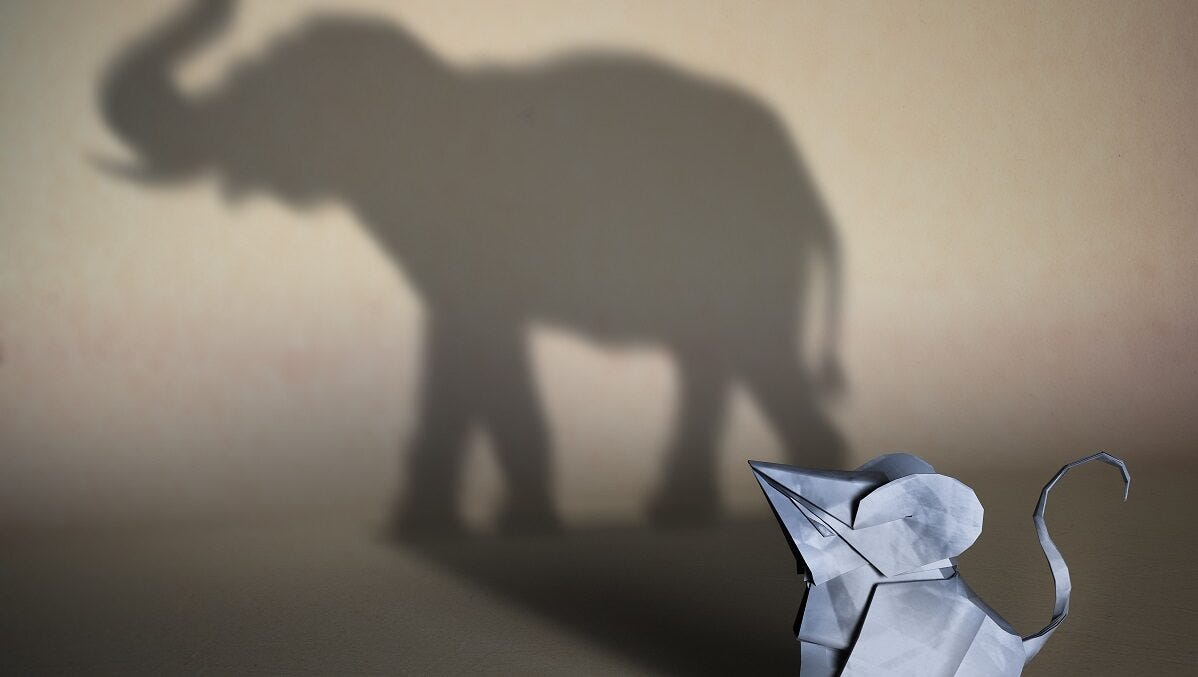

And that’s my fundamental struggle with Kalshi’s legal arguments. There’s a quote that comes up often in administrative law: Congress “does not … hide elephants in mouseholes.” (You may remember that line in such briefs as the Casino Association of New Jersey’s amicus brief.) It’s the idea that, if Congress really wanted a federal agency to do something big, you shouldn’t have to work very hard to find the agency’s authority to do that thing.

Yet that’s what we’re seeing in court, and in position papers like the Aron and Jones article. With equal parts stridency and sharp lawyering, we’re watching prediction markets contort themselves, trying to fit sports contracts squarely within the CFTC’s authority – and only the CFTC’s authority. Those who support the CFTC’s oversight of such contracts say you can find an economic consequence for any sporting event if you squint hard enough – but the point is that you shouldn’t have to squint. There are serious questions about whether the fit is right; courts have managed to overcome these obstacles by overlooking them.

I see the practical reason why both Judge Gordon and Judge Kiel ruled the way they did: nothing’s lost by ruling for Kalshi, at least temporarily, to buy time. For his part, Judge Kiel reserves the right to change his mind later: “a finding of likelihood of success on the merits here does not prejudge a finding for defendants through dispositive motion practice or trial.” Judge Gordon made similar statements.

But hard cases make bad law, and bad law tends to snowball. Kalshi will doubtless cite the New Jersey win in its papers before the Maryland court; to Kalshi, it’s the W, not the play-calling, that matters. And if you’re representing the State of New Jersey, you’re left wondering whether you’ll have a fair opportunity to change Judge Kiel’s mind on the law – or whether you’re better off trying to stop the snowball on appeal.

Although I have serious doubts about Kalshi’s legal arguments, it may well be right at the end of the day. (I’ll need a prediction market to be sure.) I just wouldn’t put too much stock into decisions that do little to answer the questions on all of our minds: where, exactly, do we draw the line, if there’s a line at all? The sooner we have judicial decisions willing to answer the hard questions presented by Kalshi’s hard cases, the better off we’ll be – all of us, including Kalshi.